Medusa

Artist: Unknown

Media: Painted terracotta

Date & Location: Around 500 BC, Italy

Where can I find this item?: The British Museum

Image Source: Photo by the author

(This object was included in the exhibition “Feminine Power: The Divine to the Demonic” at the British Museum, which ran May 19th to September 25th 2022)

♥Trigger warnings for mentions of sexual assault♥

Significance to Queer Art History

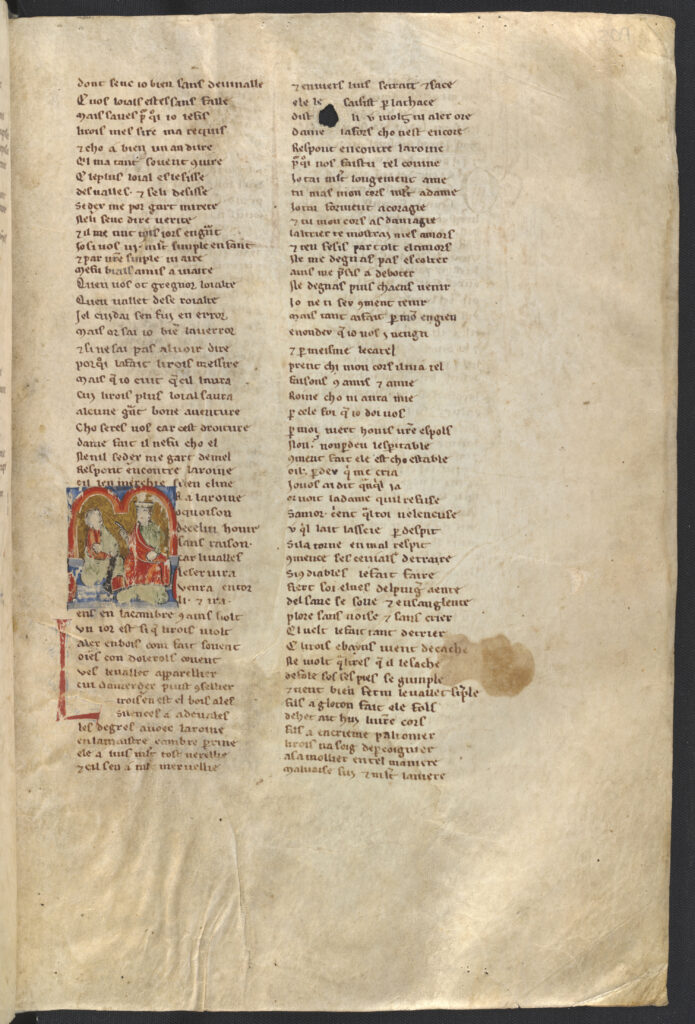

This relief sculpture shows the famed Medusa with her characteristic serpentine hair as well as a beard and tusks, which is not uncommon for images of her made in Ancient Greece. Gorgoneion is the term used to describe these ancient images of her severed, serpentine head. Since Medusa’s image was believed to possess protective powers these objects were thought to be imbued with apotropaic (or protective) qualities and this one was likely mounted on a roof to serve this purpose.

In Greek mythology Medusa is one of the Gorgon sisters born to two sea gods, Keto and Phorkys, and is famously killed by Perseus who reflects her gaze in his shield. Upon her death, her children Pegasos and Chrysaor spring from her neck and her decapitated head retains its powerful deadly gaze. Roman mythology adds that her transformation from mortal human to lethal legend was her ‘punishment’ after she was raped by Poseidon in the temple of Athena.

She is often taken up as a feminist symbol. Her hybridity, transformation, and the queer mode through which she creates her children also have queer potential. These bearded early representation further take this legendary figure beyond binary bounds. Anne DeLong (2001) compares the snakes in Medusa’s hair to the bearded witches in Macbeth for their mutual refusal of hegemonic femininity, and these bearded Medusa-figures certainly strengthen the bond between these temporally dispersed figures who are linked in lore through their body hair. They all have a place in the ever-growing archive of defiant, dangerous, protective, and powerful queer bodies that can be found throughout hirstory.

Resource(s)

British Museum, “Divine Femininity: The Divine to the Demonic,” exhibition and catalogue, May 19th to September 25th, 2022.

British Museum, “Antefix,” accessed 2022-06-26.

DeLong, Anne M. “Medea and Medusa: The Archetype of the Witch in Literature”. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2001.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Medusa in Ancient Greek Art,” accessed 2022-06-26.